Trusts and foundations offer a range of succession, wealth planning and philanthropic solutions for individuals and families.

Asset protection and taxation are likely to be important considerations when considering the merits of establishing such structures.

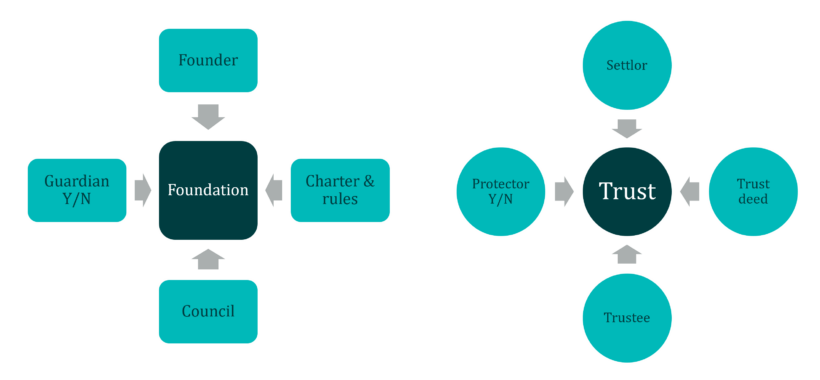

Broadly, a trust is a relationship between three parties: the settlor (who creates and transfers property to the trust), the trustee (who receives the assets) and the beneficiaries. Once a trust is established, the legal ownership of trust property will vest in the trustee, who has a fiduciary duty to hold and manage the trust fund in the best interests of the beneficiaries. In doing so, the trustee will need to take account of the provisions of the trust deed and any non-binding ‘letter of wishes’ from the settlor.

Conversely, foundations are separate legal entities incorporated on the instructions of a founder. A foundation is particularly attractive for clients from civil law jurisdictions, which normally do not recognise any distinction between legal and beneficial ownership. A foundation owns any property transferred to it by the founder and is managed in accordance with a charter and rules. In common with a trust, a foundation must have clearly defined objects, which can be either charitable or non-charitable.

Foundations have no beneficial owners, but the founder may choose to reserve certain powers, for example the power to manage investments or to make distributions. Reserved powers may also be found in trust deeds, although their nature and extent varies considerably. Caution should be exercised when incorporating reserved powers in a trust deed, since in extreme cases they could be such as to render the trustee a mere nominee of the settlor, thereby negating the tax and asset protection benefits of the structure. Ultimately, the extent to which the settlor wishes to reserve powers (for themselves or another person) may reflect a range of factors, and these will need to be considered in the round.

The illustration below outlines the parties to both structures.

Foundations and trusts are flexible arrangements. Typically, they operate on a discretionary basis (with the council/trustee determining what benefits are to be provided, and to whom). However, it is also possible for a particular beneficiary to be given a right to income arising from part or all of the underlying fund.

Both structures have the ability for a third party to be appointed to oversee the duties of the trustee or council – a protector in the case of a trust and a guardian in the case of a foundation. A protector or guardian may have powers of veto in respect of distributions. The extent of his or her powers will be incorporated into the trust deed or rules.

It is important to consider beneficiary rights to information in the context of trusts and foundations. Whilst a trust beneficiary would ordinarily be entitled to certain information concerning the trust, the regulations of a foundation can be drafted so that there is no requirement for beneficiaries to enjoy such a right. The Guernsey Foundation Law differentiates between enfranchised and disenfranchised beneficiaries in this regard. It should be noted that where there are disenfranchised beneficiaries, a guardian must be appointed.

When reviewing the issues of residence and governance, it is important to note that it is not necessary for a trustee to be resident in the jurisdiction of its proper law. For example, the trustee of a Guernsey law trust might reside in Switzerland. However, in such a case it will still be desirable for the trustee to have a good understanding of Guernsey law, so that they can properly discharge their duties under the trust deed. Conversely, a foundation is registered upon incorporation and must have a physical registered office in the place of incorporation.

A foundation is often described as a hybrid of a trust and a company. The directors of a company oversee and manage the company’s activities, just as the council does for a foundation. Separate legal personality is also a key similarity, with both companies and foundations needing a physical registered office. This is another reason why civil law jurisdictions may opt for a foundation rather than a trust, as the corporate structure is more clearly understood.

In summary, whilst there are many similarities between trusts and foundations, there are also important differences. Trusts are generally better suited to the needs of families based in common law jurisdictions like the UK, where the tax rules typically accommodate such structures and there is a body of case law on which reliance can be placed. Conversely, for those residing in civil law jurisdictions (many of which do not even recognise the concept of trusts) foundations will usually be better understood and more compatible with local tax regimes. However, each case will need to be considered on its merits, taking into account legal and taxation rules, cultural norms and any practical considerations arising from residence in a particular country.